Pierrfect

Pierre Rutagaya is a sophomore student with albinism at West High.

There are approximately 330 million people in the U.S., yet only about one in 18,000-20,000 have a form of albinism, according to the National Organization for Albinism and Hypopigmentation. Pierre Rutagaya ’24 happens to be one of them.

Rutagaya believes that its rarity results in a broader issue regarding the lack of education about albinism.

“It’s not really taught like that,” Rutagaya said. “Besides animals in science, I’ve never heard about [schools] teaching about human albinos.”

Albinism is a genetic condition that can affect all sexes and races. Albinism, however, is only an umbrella term that describes a diverse condition with various advantages and disadvantages. For Rutagaya, one advantage is how unique it makes him.

“I guess it means a lot that I’m not the same as everybody else — I stand out,” Rutagaya said. “I wouldn’t change who I am. I wouldn’t want to be different because I like the way I am.”

I wouldn’t change who I am. I wouldn’t want to be different because I like the way I am.

— Pierre Rutagaya '24

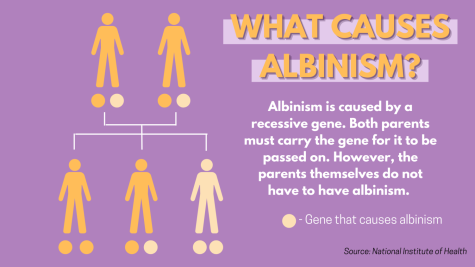

Generally, albinism reduces the melanin pigment in the skin, hair and eyes. The degree of pigmentation loss depends on the type of albinism; oculocutaneous albinism involves eyes, hair and skin, while the less-common ocular albinism affects only the eyes. Because of these physical differences, those with albinism sometimes face curious questions from others.

“[People say] stuff like, ‘Where’d you come from?’, ‘How did you get this type?’ They just ask random questions, basic questions that people are supposed to know,” Rutagaya said. “When people ask [these] questions, I don’t like answering them just because I feel like this is basic knowledge that people are supposed to know.”

These questions can stem from an ignorance surrounding albinism. Certain African countries have a superstition that the body parts of people with albinism have special powers and therefore use them in witchcraft. This leaves those with the condition living isolated and in fear for their lives. Fortunately, Rutagaya’s case is not as intense.

“Most people don’t bring it up. They just treat me as a normal person. But most people have questions. They want to know what it is. I always answer,” Rutagaya said.

Still, to Rutagaya, even excusing questions as mere interest should have a limit.

“Sometimes it gets annoying,” Rutagaya said. “But sometimes, some people are just curious.”

Rutagaya finds that people compare him to others with albinism and tend to generalize who they are and how they look.

“We’re all not the same person. We’ve got different features and stuff like that.”

Rutagaya sometimes finds himself a victim of ridiculous questions and assumptions from those around him.

“I used to get like, ‘Did you bleach your skin?’ … ‘Did your mom sleep with a white man?’” Rutagaya said. “I haven’t heard these questions in a minute.”

Rutagaya’s friend, Clinton Carter ’24 also recalls hearing some of these ignorant comments from a peer.

“It [happened] once, but I knew he was joking. He was probably like, ‘That’s why you’re albino’ or something,” Carter said.

To Rutagaya, many of these questions seem to have an obvious comedic intent.

“They just like making jokes. I think people can just choose to be ignorant,” Rutagaya said.

People with albinism face physical challenges due to their condition as well — they have skin that is highly sensitive to the sun and vision problems that are not always repairable with eyeglasses. In fact, the abnormal retina development and nerves that connect the eye and brain are what formally define whether someone has albinism or not. Common problems that result from the altered development include astigmatism, poor eyesight, photophobia and nystagmus. Otherwise, those affected have average lifespans and carry out regular lives.

“I was just treated differently because I was different from others,” Rutagaya said. “You have got something to prove, I guess.”

I was just treated differently because I was different from others. You have got something to prove, I guess.

— Pierre Rutagaya '24

Despite one in 70 people carrying the genetic mutation associated with albinism, Rutagaya has still found himself alone in having the condition because of its recessive gene nature. Even on the streets of New York, where he used to reside, he had never caught more than a glimpse of albinism around him.

Regardless, Rutagaya is surrounded by a supportive group of friends and peers, with Carter being one of them.

At the end of the day, albinism is a condition that affects physical characteristics. On the inside, we are all the same.

“I don’t really see anything different about him. He’s just like me,” Carter said. “[Seeing him treated differently] makes me kind of confused because at the end of the day, he’s still a person, so it’s kind of disappointing.”

Your donation will support the student journalists of West High School. Your contribution will allow us to purchase Scholarship Yearbooks, newsroom equipment and cover our annual website hosting costs.

Ruba Ahmed is a senior at West High. This is her second year on the newspaper staff and she is profiles co-editor as well as business co-editor. Outside...