Umachina: Golden child, the origin story

The perfect golden child that can do no wrong and whose shadow we live in— Everybody comes across one at least once in their life. but we never consider who resides in our own shadows.

The golden child may appear as an untouchable and glorious title, but all trophies just gather dust while stuck in a glass case.

I am eight years old, sitting on the faux leather couch next to him as our mothers chat over coffee in the room next door. We’re both silently watching TV, but the voices are too loud to ignore—for me, at least.

Comments about how well the child next to me is doing at school, how he’s learning piano and improving his English every day, how he must’ve grown five inches since we’ve seen him last. My name is also mentioned occasionally, but only as a casual remark about how much trouble I stir up at home— not to insult me, but obviously not to praise, either. I don’t want to look him in the eye because of how embarrassed I am; I’m not sure of my mother or myself. All I know is that there is no way I could ever live up to him, my mother’s friend’s son, the umchina.

Umchina (엄친아)— roughly translated from Korean to mean “My mother’s friend’s son.” Used as slang to describe a hypothetical “perfect child” with absolutely no faults. Except that, at times, the hypothetical often replaces reality. This phrase may be limited to Korea, but the experience of being compared to another is universal to any and all cultures. No matter what you do, you can’t live up to their legacy; worse, your mother can’t shut up about them.

“My mother’s friend’s son.” Used as slang to describe a hypothetical “perfect child” with absolutely no faults. Except that, at times, the hypothetical often replaces reality.

— Nicole Lee '24

They mean well, most of the time. Unfortunately, the truth is many mothers rave about the umchina as a way to motivate their own children to succeed, but what ends up happening is that they invalidate the child’s sense of accomplishment and lead them to believe they will ever be good enough. How often have I joined an extracurricular because my umchina was also a member? Compare my grades to them in class? Act like I don’t recognize them in the halls because I don’t want to see how well they’re really doing? The bane of my existence, not because I hate them but because my mother doesn’t.

It doesn’t matter how far I’ve come when they always seem farther. The strange thing about Asian parents is that they want you to succeed but fail to see it when you do. It’s almost like a blindspot for them; all they can see when they look at you is something that can be improved upon. Something can always be better. You can always be better. An unachievable goal because it never ends. You will always have to try and reach the high branches that are their expectations, but the umchina is already the entire tree. How are you ever supposed to beat them?

Something can always be better. You can always be better. An unachievable goal because it never ends.

— Nicole Lee '24

I’m seventeen years old now, and I’m sitting on the vinyl couch next to him as our mothers chat, preparing lunch upstairs in the kitchen. We’re all watching movies together until we’re called to the dining room. The mothers continue to talk as we’re eating, almost as though we aren’t there. Something is different, though. The conversation isn’t what I’m used to.

“Look at Nicole; she’s become such a fine lady.”

“Your daughter is so respectable; you must be proud.”

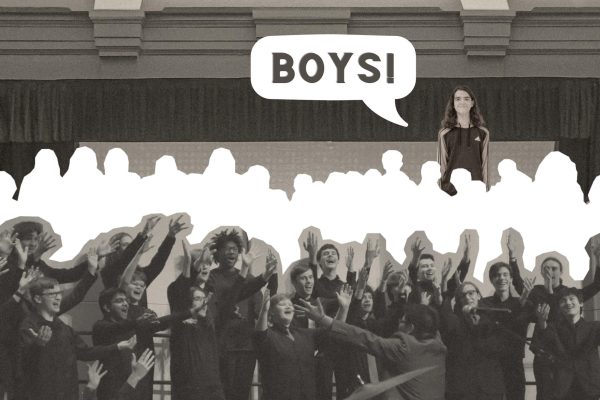

“She’s doing so great at school; you should be more like her.”

We are sitting right next to each other, but I suddenly found myself on the other side of the discussion. I look over to see him with the same embarrassed expression I used to wear when I was his age. That is not the expression an umchina wears— because he is not the golden child of this story. The comments keep coming, and I’m flattered while trying to stay modest. And yet I cannot ignore this overwhelming sense of guilt. My mother’s friend hardly gives her child the same attention she is giving me, which may be why she doesn’t notice how quiet he’s gotten. I can hear his silence, however. I couldn’t ignore it if I could try.

And just like that, the tables have turned. Now it is my time to be the child to which parents compare their children. The child who knows how to respect her elders and mind her manners; always gets compliments from her teachers at school; receives awards for her writing; has extended knowledge of books and films; is practically perfect in every way.

Perhaps I felt smug in the beginning. I enjoyed the attention I received because I felt I had earned it through my hard work. But that very praise came at the sake of other children. Without even realizing it, I had trapped others in my shadow, forcing them into the same competitive cycle that is a struggle to escape.

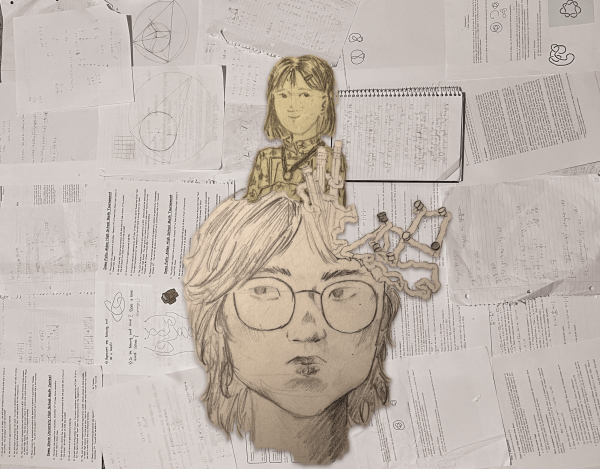

Because even by that point, I myself had yet to escape. The rest of the parents from my family’s friend group might have patted me on the back for my accomplishments, but they weren’t the people I cared to impress. Nobody knows you as well as your own mother, and in her eyes, I could still be better. None of it mattered; I may have taken over the role of umchina, but I was still in the same place as before. I continued to compare myself to others; my umchina was still a part of my life, only now, I couldn’t hold it against them because I was in the same position.

None of it mattered; I may have taken over the role of umchina, but I was still in the same place as before.

— Nicole Lee '24

We are all inclined to believe that the supposed golden child with no faults probably has no concerns either, but that isn’t true. They are also a result of their own troubles and insecurities. In this age of mental health awareness, people are already familiar with the idea of experiencing burnout starting from as young as high school. Students are forced to spread themselves out incredibly thin because they are led to believe that is the only way to get anywhere in life. We’ve all met those former child “prodigies” who are under the pressure to still maintain the status of being able to exceed expectations only to be hit with the harsh reality that they may be “average.”

What we seldom realize, though, is that unintentionally, we all trap ourselves and each other in these cycles of stress. By trying to escape the other’s shadows, we force someone into our own. And it all begins when someone like our very parents, also blinded by the drive to succeed, try to push us over the edge by causing us to see our peers as rivals. The truth is, there’s a very good chance my umchina was also compared to other children by their mothers and the same to those children. The person I believed was an obstacle in my academic life was actually focused on their personal obstacles as well, in the very same race. And I only came to realize that when I found myself in their very same shoes and contributed the very environment that suffocated me for years.

By trying to escape the other’s shadows, we force someone into our own.

— Nicole Lee '24

With the younger generation comes a new age. If we ever want to break out of this cycle of toxicity, we have to acknowledge that we are only responsible for ourselves. Or else we’re just letting others step in the same footsteps we tripped on over and over when we were following the people before us. Instead of just taking the one path shown to us, it should be taught that one is perfectly capable of diverging onto a path that is just their own. No more standing behind someone and never seeing what’s ahead of you.

Your donation will support the student journalists of West High School. Your contribution will allow us to purchase Scholarship Yearbooks, newsroom equipment and cover our annual website hosting costs.

(she/her) Nicole is a senior and in her third year on staff and second year as opinion editor. You can usually spot her walking down the hall wearing her...

(she/her) Ashlyn is a junior and this is her second year on staff. She is the Feature Editor for the website this year. When she's not in the newsroom,...