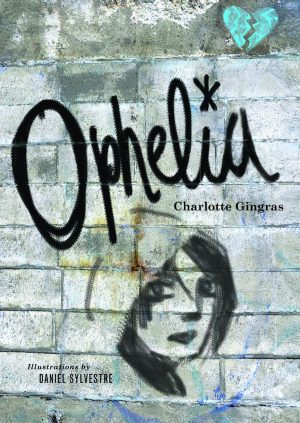

Set me free: an “Ophelia” review

Charlotte Gingras’ novel, originally published in French, presents an intimate and raw portrait of a girl trying to survive a rough life by expressing herself in frescoes.

My prior experience with a translated novel wasn’t pleasant. Granted, it was “The Princess Plot,” and the only thing I remember was that the cover was pink and had black skulls, the mother got kidnapped and the princess chopped off her hair so she could play a boy. I remember being very upset about the last point. Don’t ask me why.

Regardless, a bookseller set this advance copy aside for me because she believed I would like it. I was intrigued by the blurb and the fact it was originally published in French ten years ago. It was also inviting to see a story about embracing art and a hesitant friendship. What did I have to lose? I picked this one up and gave it a go.

If there’s one word that comes to mind when I think of “Ophelia,” it’s unique. I’m certain everyone at some point has read a story where a girl confides in a journal. But here, there’s a raw ache that permeates the narrative and makes it that much more memorable. The writing flows in such a graceful stream of consciousness as Ophelia navigates her insecurities and pain while living her life. There’s an appreciation for art and writing that I respect wholeheartedly, and the evolution of Ophelia as she accepts who she is and those around her is heartwarming.

However, it also comes across as somewhat jarring, considering the narrative this book follows. A lot is contained within Ophelia’s diary pages, including a first crush, contempt for the popular kids at school, her job and a mom that’s still recovering from a drug stint while finding love. Additionally, Ophelia’s friendship with Ulysses feels toxic. A lot of their initial interactions are based on insults and judgment, and it makes me uncomfortable. Still, those looking for a quick read complemented by illustrations may find something in “Ophelia.”

There’s a raw ache that permeates [“Ophelia”] and makes it that much more memorable. The writing flows in such a graceful stream of consciousness as Ophelia navigates her insecurities and pain while living her life.

— Luke Reynolds

Ophelia has hidden herself for almost her entire life. The kids at school call her Rag Girl because she buries herself in clothes twice her size and rarely talks. However, she breaks her silence when a famous author visits her school and she asks the first question. The author, Jeanne D’Amour, is so flattered by Ophelia speaking up that she gives her a blue notebook. Ophelia writes letters she doesn’t intend to send to this woman, thoughts about the people around her and why she chose Ophelia as her name to further hide herself. She also confesses to spray-painting broken hearts onto random walls around town, leaving her mark so she can be remembered once she’s gone. One day, she finds an abandoned warehouse that could serve as the perfect artistic refuge. However, she soon discovers she isn’t alone. Ulysses, another classmate who spoke out at the author visit, has found peace as well, trying his best to fix an engine on an abandoned truck he calls Caboose. He’s just like Ophelia when it comes to being a recluse at school, the bullies turning on him due to his weight. Although they start off on rocky terms, they gradually begin to realize there’s strength to be found in their pairing. They may be the only ones who can accept themselves and each other in such a cruel world.

As you can see, this novel gets pretty heavy. Gingras captures Ophelia’s depression in stark detail, whether it be with sentence fragments or long tangents that let themselves run free. A reader understands her anger at those who are better off than her, and the way she describes her day-to-day life is buoyed by her emotions and is elevated because of them. I love Gingras’ focus on creativity and how you should never be afraid of expressing yourself through something as abstract as a painting or a daily journal. Gingras’ background is in art and writing, so perhaps this is preaching from her popping up in the book, but I respect this focus because it makes my creative soul sing.

Despite its initial toxicity and insult-sharing, Ophelia’s friendship with Ulysses really anchors this narrative. Ophelia’s begrudging acceptance is slow but realistic, especially since the two of them have been outsiders their entire lives. While I do feel her official toleration is abrupt, not only does it flesh out the thematic arc of accepting the world, but it also highlights character development. The Ophelia at the beginning of the book wouldn’t have broken out of her shell to care about someone. However, she learns to.

Unfortunately, what sours this book in my mind comes in Ophelia’s opinions and attitudes towards people. I’m aware this is in no way the author letting her opinions decide how her protagonist should behave. Ophelia is the classic moody 15-year-old girl we’ve all known and have been. But it still makes me uncomfortable to see her wondering how a girl can fall in love with another girl and voicing her opinions on why a Muslim woman shouldn’t wear her hijab. Maybe these views are a product of the culture this book is set in, that of French Canada. However, my discomfort still lingers past the last page.

Even the illustrations peppered throughout “Ophelia” feel tired by the end of it. Daniel Sylvestre’s visually arresting collages and illustrations start off strong, but by the end, a 10-page swath of them lose my interest and make me want to go back to the narrative. They don’t feel like they add anything to the story at the end, even though they should.

But at the end of the day, Charlotte Gingras‘ “Ophelia” is still a captivating read for those who love voice-driven accounts on life. Gingras won an award back when this was originally published in French for a reason. I respect it but don’t love it, yet I’m glad to have experienced something raw and different.

Your donation will support the student journalists of West High School. Your contribution will allow us to purchase Scholarship Yearbooks, newsroom equipment and cover our annual website hosting costs.

This is Luke's first and only year as a member of West Side Story. He'll be kept busy with anchoring, editing and reporting, but he's gonna have fun while...